Tom Gallagher is Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Bradford. His book Europe’s Leadership Famine 1950-2022: Portraits of Defiance and Decay was published on 22 June. A biography of Portugal’s enduring 20th century leader, Salazar, the Dictator Who Refused to Die,was published by Hurst Publishers in 2020 and his twitter account is @cultfree54

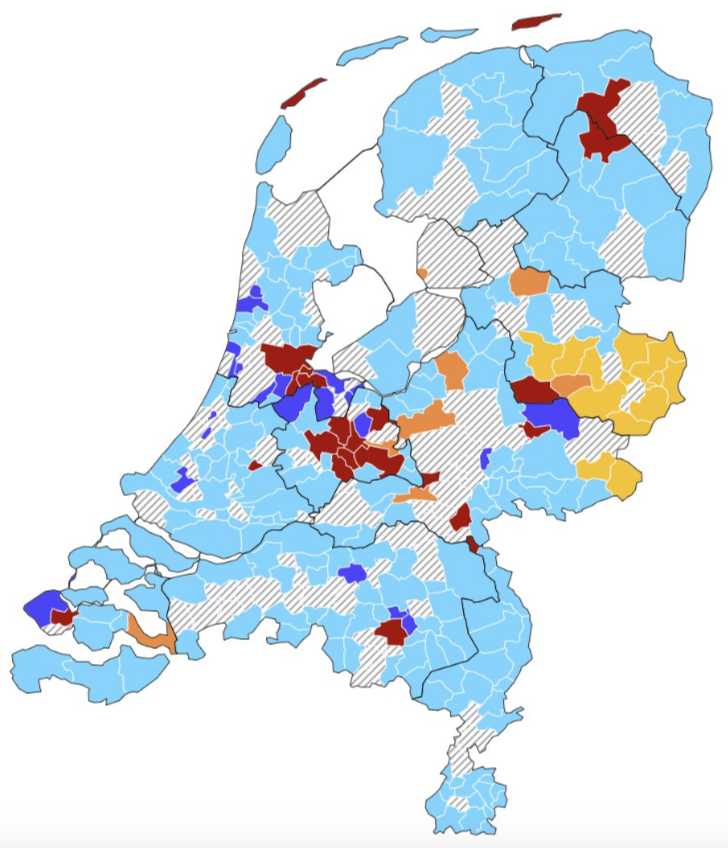

The areas of the Netherlands coloured light blue were the ones which voted for the PVV on 22 November.

Geert Wilders, who led a rebellion of Dutch voters on 22 November against an urban ,left-wing and globally—focussed managerial elite, didn’t appear before a cheering multitude as the scale of the electoral earthquake in the Netherlands became apparent. After the first exit poll showed that most parts of the country had voted for the Party for Freedom (PVV) outside the biggest cities, viewers were treated to an unusual sight. It was that of an animated guy wearing a blue suit and red tie, and in quite good shape for someone of 60, jumping up and waving his arms in evident joy, at the news of the not-so-small earthquake just registered in Holland.

There was almost something of the Man in the Iron Mask emerging blinking into the day light from captivity contained in this shot, for Wilders has been under tight police protection non-stop since his mid-forties. It is a remarkable state of affairs for any European country but almost unfathomable for one like the Netherlands where freedom has been so highly regarded.

His brother recently told Der Spiegel: Geert’s world has become very small. It consists of the parliament, public events and his apartment. He can hardly go anywhere else.’

His uncompromising views on Islam and the danger which he is convinced that the growing concentration of its adherents pose for the Dutch liberal, secular model of existence, have provoked a wave of threats to kill him. He has also attracted the ire of leftist forces entrenched in many of the institutions who have pursued him through the courts on account of his views.

The PVV has been in third or fourth place since its formation in 2006. It was set up due to a rising gulf of mistrust between the state and a growing number of its citizens, who felt as if they had become outsiders in their own country. It never broke into front rank politics until now. Mark Rutte, a technocrat with a background in the human resources industry, enjoyed an unsually long tenure as Prime Minister, from 2010 till this summer. At the helm of the liberal free market Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), he displayed the knack of soothing voters anxieties as storm clouds built up.

The decision of this Machiavellian figure to call a snap election after divergences in his 4-party coalition on asylum policy, led to unexpected happenings. Rutte seems to have assumed that by reshuffling the coalition pack, and perhaps by ridding himself of the party of Dutch middle-class radicalism whose eco-fundamentalism had alarmed many, it would return to being business as usual.

It was a gamble given that their had been months of public uproar in normally calm parts of the country. The farming population had discovered it was the sector which was required to make the sharpest adjustments to the new Green economic model. It was one that committed the Netherlands to slashing carbon emissions and endeavouring to make Europe the poster boy for an environmentally-focused planet. In 2021-22 months of mass protests ensued due to rural opposition to closing thousands of farms in order to fulfil Net Zero targets.

This March, a new party, the Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB) emerged as the big winner in the Dutch provincial elections which decides the composition of the upper house of parliament.

But the urban-rural fracture in Dutch life was overtaken by an older one which had acquired fresh intensity midway through the election campaign when Hamas struck southern Israel on 7 October. Traditionally, the Netherlands has been very pro-Israel. Shock at the scenes of horror that lead to the slaughter of over twelve hundred Israeli civilians was followed by anger and fury when celebrations of Hamas’s ‘victory’ occurred, ones staged mainly by citizens of Moroccan or Turkish descent. These triumphalists gatherings were less numerous than in Britain or the USA and had fewer white, middle-class participants.

The readiness of various pro-Hamas zealots in the West to demonstrate their solidarity in this way made it awkward for the comeback being planned by Frans Timmermans. This ex-diplomat and former Labour party (PvdA) MP had stood down from his position as the EU’s climate commissioner as soon as Rutte called an election. He placed himself at the head of an alliance of Labour and the Green party in order to try and maximise the strength of the progressive, climate-focussed wing of Dutch politics.

The desertion of the Dutch working-class had ravaged the previously large and powerful PvdA. It increasingly drew its support from recent arrivals or unassimilated groups who retained an enclave identity. Timmermans, a bland and somewhat patronising figure, struggled to articulate an exciting coherent message, beyond the shibboleths on climate, the need for more Europe, and the importance of everyone just somehow getting along.

He squirmed as diverging reactions to 7 October led to tensions within his hastily assembled coalition of hipsters, NGO officials, academics, bureaucrats on the one hand and religious focused activists absorbed with events beyond a country whose way of life seemed strange to many of them, on the other. A disquieting incident in Rotterdam, the main industrial city, revealed his predicament. Its mayor, a Moroccan-born former journalist, Ahmed Aboutaleb, was one of the few remaining Labour figures who exercised real power in the country.

His decision to refuse to fly Israel’s flag from the town hall as a mark of sympathy after 7 October caused a stir. It played into the hands of Wilder’s formation, consistently pro-Israeli in its stances which doubled its vote in Rotterdam and became its largest party on 22 November. Beforehand, instead of doubling down on his anti-Islam rhetoric, he adopted a milder stance. He stated his willingness to draw back from several of his outspoken views which included a ban on Islamic schools and mosques if it increased the likelihood of non-left parties having him as a partner in a new coalition.

His offer to work with others on a common agenda to fix the country and trim the influence of out-of-touch groups in the bureaucracy and corporate institutions whose policies were demoralising many voters, struck a popular chord, as it was bound to do.

On issues like climate policy and managing immigration, the Dutch metropolitan elite was forthright about replacing identities shaped around loyalty to a fixed territorial community with commitment to building a new progressive global order. It did not flinch from backing schemes which required major adjustments in lifestyle and occupation from Dutch citizens. The ability of the state to lockdown the country during the 2020-21 Covid pandemic seemed to prove that the status quo could weather even the farmers protests. Rutte’s globally-minded liberal alliance did well in a parliamentary election called in March 2021 as elder voters in particular craved the certainty that this smooth operator offered.

But the Netherlands had also seen the fiercest riots anywhere in northern Europe against the lockdown regime. It took Rutte nearly eight months before he could form a government, and he alienated a party stalwart Pieter Omtzigt. He stood for national Liberalism rather than Rutte’s global variety and the New Social Contract party which he formed this summer, came in fourth this week.

This decent but lugubrious figure was too close to the status quo to appeal to the young. At the end of 2022, a survey revealed that 50 percent of young people believed that things are ‘going in the wrong direction in the Netherlands’, up from 38 percent in 2018. Results from school elections this year show that school attendees are more conservative in their outlook than the population at large (a complete contrast with Britain).

What happened in the closing days – indeed hours – of the campaign was a massive shift in preferences. It seemed there would be 3 main blocs, the left, the liberal VVD, and the party of Wilders, each with around the same voting percentage. But it turned out that many people were masking their true voting intentions even to friends and neighbours. Many of the unusually large ‘don’t knows’ whom pollsters encountered were in fact going to vote PVV. They were people who felt that enough was enough and something would have to change in order to stem the drift towards social polarisation and rule of a fragmented and unsafe country by unaccountable overseers.

As a result the PVV vote soared from 11% to nearly 24%, shocking even Wilders himself. This was the largest swing recorded in any Dutch election in the last eighty years (other than for new parties). Only cities like Amsterdam, Utrecht, and the Washington DC of Holland, the Hague (home to an increasingly overbearing state), withstood the PVV wave (as did smaller university centres).

These were the strongholds of progressives grimly intent to impose a design for living on the whole of society based on radical precepts that only a minority embraced. But even the anti-globalist socialist party saw a huge exodus of votes towards the PVV.

Geert Wilders might easily feel vindicated. He had been banned from entering Britain by a Labour Home Secretary Jacqui Smith in 2008. Ten years later, Prime Minister Theresa May effectively did the same thing when her government said that he would only be allowed admission if he came without the security officials laid on by the Dutch authorities to ward off physical attack.

The parties in the outgoing coalition saw their voting total fall from 49 to 27%. Inevitably, attempts will now be made to form an unwieldy coalition of the losers. There are two likely outcomes of the horse-trading that will flow. One is a centre-right coalition including the PVV but with Wilders probably not in government. The other, perhaps the likeliest is a centre-right formation sustained by the PVV (the kind of arrangement that already exists in Sweden).

Postscript: A polling survey carried out on 23 November found that 84% of voters from the VVD, 78% from the National Social Contract (NSC ) and 99% from the BBB wer2e happy to see their party enter a coalition with the PVV.

If Wilders decides to exercise power from the sidelines, he will naturally drive a hard bargain. He can rightly say that the electorate have rejected by a massive margin the policies pursued by the former ruling caste, centred on migration, climate, bureaucratic interference with everyday life, and more Europe. He wants to end adherence to the outmoded United Nations refugee statutes, various climate conventions that Timmermans tried to impose on the country when he was the ‘Pope of climate change’ in Brussels, expand oil and gas extraction in the North Sea and stop deploying massive subsidies to wind and solar parks.

Wilders is already being dismissed as the Dutch Trump but he has been active in politics since Trump was busy donating to the US Democratic Party. His constituency is a massive one. Most PVV voters did so for the first time:

‘Something has to change in the Netherlands. Wilders was the only choice for us’, one of them said.

In four of the founding EU states ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() national conservative parties increasingly dominate the political scene with left-wing parties struggling to remain on top through their domination of the media and various state institutions.

national conservative parties increasingly dominate the political scene with left-wing parties struggling to remain on top through their domination of the media and various state institutions.

If this is a season of ‘change’ elections where the voters revolt against elites who plainly don’t have their interests at heart, what has just happened in the Netherlands is surely a vivid example of the power the ballot box still has, at least in some significant European countries.