Part 2: From the Elections of April 1975 to the Close of the Revolution

Tom Gallagher

Tom Gallagher is Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Bradford. His book Europe’s Leadership Famine 1950-2022: Portraits of Defiance and Decay was published in 2023. He has published several books on modern Portugal and he is working on a new one provisionally entitled, Portugal and the Modern Western Journey: Adaptation, Resistance and Disenchantment, 1890-2025

On 25 April 1975, one year to the day after the military coup which removed Portugal’s civilian authoritarian regime9, voters flocked to the polls to decide the composition of a constituent assembly meant to create the new architecture for a democratic Portugal.

The vacuum that had opened up in the previous twelve months enabled the Communist Party (PCP) to fill many positions of power. Politicised army officers either acquiesced in this power-grab or else seemed dazed about how rapidly the political pendulum had swung in Portugal. The new centurions who had set up a Council of the Revolution felt that what Portugal needed was a form of Third World socialism which they had dubbed ‘popular power’.

But in the event, the people could not be restrained. No less than 90 percent of adult Portuguese turned out to vote. Non-communist parties secured nearly 70 per cent of the vote. The communists and a front party were left with only 16 per cent.

Álvaro Cunhal , the dogmatic head of the PCP, was undeterred. He continued to make it clear that the influence of his party was measured not through votes but by the intensity of the struggle. The vast nationalisation programme being spearheaded by the party’s militants convinced his followers that the revolution was irreversible and that elections were ephemeral.

Since the previous winter, the PCP had been busy trying to acquire full control of the trade-union world. Increasingly, sackings and far from spontaneous occupations by printers were ensuring that nearly all of the media was heading the same way.

Curators of revolutionary nostalgia in 2024 are unlikely to linger over the overt communist power-grab that intensified after the April election. The Communists were soon locked in mortal combat with the pluralist Socialist Party (PS), which had won 39 per cent of the vote. Headed by the gregarious lawyer and long-term oppositionist Mário Soares, his manner was deceptively mild. Henry Kissinger had dubbed him the Kerensky of Portugal, someone likely to be a victim of the Marxist juggernaut as the Russian who preceded Lenin as ruler of Russia was.0 But the affable Soares had an iron will and a sharp intuition enabling him to respond rapidly to shifting events. He refused to be brow-beaten when Cunhal ordered that he be barred from entering the football stadium where the other leaders of the country had assembled on 1 May to mark Workers day. Later on 6 November 1975, he might be said to have obtained his revenge when he eclipsed Cunhal in a gripping televised debate between them. An aggressive Soares wrong-footed his adversary, claiming that it was his intention to establish a communist dictatorship, prompting Cunhal to reply ‘look it isn’t so, look it isn’t so!’

https://arquivos.rtp.pt/conteudos/frente-a-frente-mario-soares-e-alvaro-cunhal-i-parte/

https://www.newsmuseum.pt/en/duelos/ps-e-pcp-sit-table

In the preceding months, Soares then showed grit by organising well-attended protests against the media crackdown. He displayed resourcefulness by brokering alliances with conservative forces in the small-holding and Catholic northern two-thirds of Portugal.

Cunhal under-estimated the threat posed by the resilient Soares to his dream of creating a communist order on the western shores of Iberia. His grip on a party, where he was a godhead enjoying cult status, was so absolute that nobody could point out the signs that his maximalist power-grab was in danger of backfiring.

In an interview published on 6 June 1975, he contemptuously dismissed the elections held on 25 April:

‘The elections have no importance for me, nothing. If you think that the question can be reduced to percentages of votes received by one party or another, you are deceiving yourself badly’.

Within a month, this communist chieftain was finding himself squarely on the defensive. Popular resistance flared up when attempts were made to seize family farms in the centre of Portugal. The second half of the summer was marked by mounting unrest across the north. Well-attended and broadly-focused rallies protested about the impending arrival of a fresh dictatorship. Already there were more political prisoners locked up than there had been at any point under the 1933-74 New State regime. Numerous communist offices were sacked. Cunhal suffered the humiliation of being driven out of the town of Alcobaça on 18 August 1975 when he tried to hold a rally in the teeth of local opposition.

It is bound to be painful for carriers of the revolutionary flame fifty years on to reflect, in moments of candour, that their self-destructive feuding was chiefly responsible for the demise of the revolution.

The forces of the left have subsequently buried their quarrels. They have sought to dominate the well-resourced state bodies that were later created by liberal conservatives in a rare decade of efficient rule, the improvements funded by money from the European Union (which Portugal joined in 1986). Between 2015 and 2019, the political forces which had denounced each other in such savage terms in 1975 actually ruled in coalition and consolidated their hold on the machinery of state. The fiesta due to be thrown by the left next week will be presided over by forces that were mutually destructive in 1975 but now seek to display unity through a synthetic act of remembrance.

It is likely that the claim the revolution was really sabotaged by Western capitalist interests will receive a fresh airing. The tendency to blame foreign machinations for Portugal’s woes is one now exhibited by the Socialist Party (PS) which0 ruled for 20 of the last 28 years. The leaders who succeeded Soares have all been further to the left. They include António Guterres, the current head of the United Nations. His open call for a world government that will manage economics and relegate national voting in the name of saving the planet from climate doom, is even more utopian than any of Cunhal’s 1975 proposals. The latest leader of the PS, Pedro Nuno Santos, first made headlines over a decade ago when he called for an offensive against German bankers whom he blamed for destroying the Portuguese economy in the aftermath of the Eurozone crisis. Electioneering aside, most historians of the period recognise that the West largely remained a bystander during months of revolutionary upheaval.

Perhaps one of the most painful facts for revolutionary nostalgics to accept is that the only time the military displayed a flair for politics was in the second half of 1975 when moderate officers were able to stop the far-left in its tracks.

Military pragmatists (still very much on the left), who had set up the Group of Nine, concluded that a ruinous national split, perhaps leading to civil-war, was a real danger unless cooler heads intervened. The infighting which had plagued the civilian left was already spreading to the military but without igniting direct clashes. Not bothering to hide his own communist orientation, Prime Minister Gonçalves gave a defiant speech in a radical stronghold on on 18 August but by the end of the month, he had been edged o50ut as prime minister.

Economic chaos and mismanagement began to affect living standards, boosting inflation and unemployment. Workers management committees struggled to preserve efficiency and the outlook was even worse in the hundreds of state farms set up in southern Portugal.

In addition, what would eventually be a refugee exodus of nearly one million white and mixed race inhabitants of Angola and Mozambique rushed back to Portugal when independence was hastily proclaimed. In Angola, they had made up one-sixth of the population, but many arrived destitute. The lands they left behind would face years of unrest and, in the case of Angola, civil war. But these downsides of the revolution are unlikely to cloud the 2024 events celebrating release from the ‘dark night of fascism’. Nor is there likely to be much reflection on the fact that there was much continuity with the past in 1975.

The alphabet soup of far-left parties and their military allies imposed the power of the state over the economy and civil society far more completely than had been the norm under the dictatorship. In any ways, the ‘popular power’ supposedly at the heart of the revolution could be seen as a left-wing version of the economic dictator Salazar’s corporativism.

Right-wing groups emerged to challenge the stalled revolution, but it was ferment on the left which increasingly grabbed world headlines. Young ultra-leftists seized more enterprises and state facilities in a challenge to the government by now under a moderate admiral, José Pinheiro Azevedo. In the late summer of 1975, huge demonstrations occurred in Lisbon, their size augmented by left-wingers elsewhere in Europe convinced that a second Bolshevik revolution was unfolding. In October 1975 there seemed a real possibility that a commune would be proclaimed in Lisbon. The non-communist parliamentary deputies made plans to retreat north. Other plans to cut communication links between Lisbon and Porto were at an advanced stage.

But suddenly on 25 November the revolutionary music stopped. Far-leftist soldiers were confronted and disarmed and their barracks occupied by moderate units. To the surprise of many, Cunhal demobilised thousands of cadres rather than slugging it out with ‘reactionaries’. Big names in the MFA lost their positions. But the Communist party wasn’t outlawed nor indeed were most of its power-bases taken from it.

It seems there was a behind-the-scenes deal between military pragmatists and the dogmatic Cunhal. The far-left would be permitted to function in the new democracy provided it shelved its Leninist plans to seize power.

He condemned the 1976 Constitution as a surrender to darkest reaction, but it committed Portugal to continuing along the socialist path. The first elected President, an army officer Ramalho Eanes talked about building socialism and had no qualms about paying a state visit to Czechoslovakia.

Perhaps unsurprisingly the 25 November event has always been ignored by the custodians of the revolutionary flame. It is also brushed aside in school history manuals. The outgoing minister of culture Pedro Adăo e Silva has defended this exercise in myopia, saying that ‘we must celebrate what unites us’. It means there will be no awkward spotlight on the actions of those who couldn’t stomach the idea of a liberal democracy taking root in Portugal.

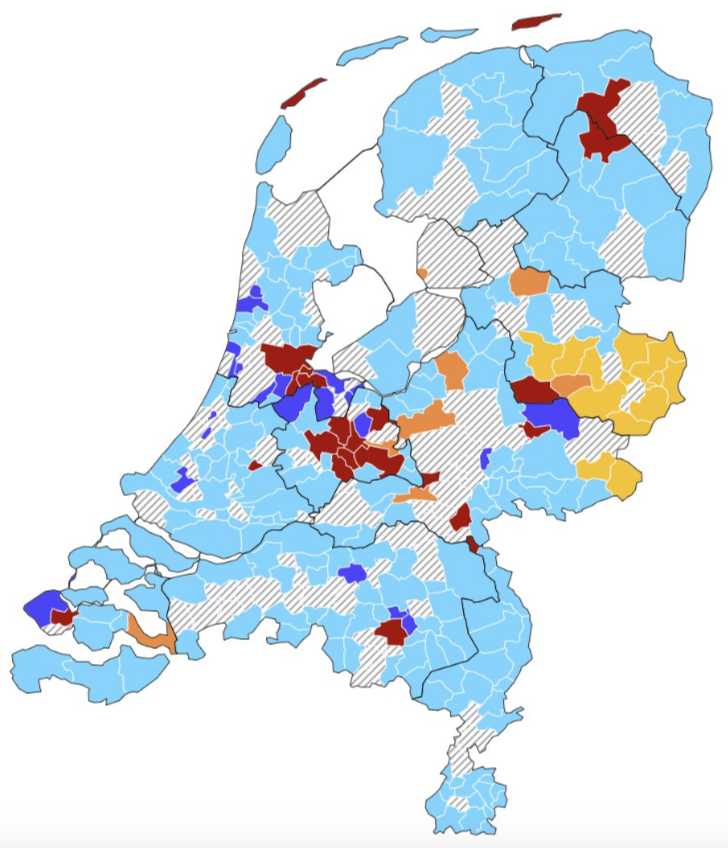

The Socialist government has been the chief choreographer of the planned pageant. But it has been in increasing disarray. Corruption scandals and chronic incompetence in handling state affairs have led to growing discontent. Much of it has been channelled into support for the populist right-wing Chega party. In a parliamentary elections held on 10 March, the Socialist vote plunged from 42 to 28 per cent. Chega soared from 7 to 18 per cent, winning 50 deputies.

The revolutionary anniversary has come around just as the left has been relegatned to the opposition benches. The miserable electoral performance of the far-left parties shows there is no appetite in Portuguese society for the experimentation – this time not economic but focused instead on human nature – which progressives tirelessly advocate.

The revolution in 1975 obtained much of its drama and colour from radicals in northern Europe flocking to Lisbon to swell the demonstrations that paralysed the city during this heady but deceptive time. In 2024 these young radicals, many of whom today occupy positions of power in state and European institutions will likely celebrate memories of a rare revolution to have occurred in Western Europe. But the tide is going out for them. Many European citizens are keen to clip their wings. They are weary at the restrictions these fine-living moralists impose on everyday living by pursuing punitive policies of climate communism.

Perhaps Europe will witness a version of the struggle against quasi- revolutionary excesses which occurred in Portugal in 1975 and which foiled a takeover bid by a new set of dictators, ones far more implacable than the supposed fascists removed in 1974.

The European elections in June seem set to repeat the drubbing which the previously dominant left received in Portugal on March 10. While entrenched in state institutions the vanguard forces of the left are as unloved in Brussels as they are in Lisbon, but they can probably be relied upon to put up fiercer resistance against the many millions of people heartily tired of their guardianship.